- INTRO

- Lectures XVIIe-XVIIIe

- Lectures XIXe-XXe

- 1820-1840

- 1840-1860

- 1860-1880

- 1880-1900

- 1900-1910

- 1910-1920

- 1920-1930

- 1920s

- Breton

- Tanguy - Ernst

- Eluard

- Jacob - Cocteau

- Gramsci

- Lukacs

- Hesse

- Woolf

- Valéry

- Alain

- Mansfield

- Lawrence

- Bachelard

- Zweig

- Larbaud - Morand

- Döblin

- Musil

- Mann

- Colette

- Mauriac

- MartinDuGard

- Spengler

- Joyce

- Pabst

- S.Lewis

- Dreiser

- Pound

- Heisenberg

- TS Eliot

- Supervielle - Reverdy

- Sandburg

- Duhamel - Romains

- Giraudoux - Jouhandeau

- Svevo - Pirandello

- Harlem - Langston Hughes

- Cassirer

- Lovecraft

- Zamiatine

- W.Benjamin

- Chesterton

- Akutagawa

- Tanizaki

- 1930-1940

- 1930s

- Fitzgerald

- Hemingway

- Faulkner

- Koch

- Céline

- Bernanos

- Jouve

- DosPassos

- Kojève

- Miller-Nin

- Grosz - Dix

- Green

- Ortega y Gasset

- Wittgenstein

- Russell - Carnap

- Artaud

- Jaspers

- Sapir - Piaget

- Guillén

- Garcia Lorca

- Hammett

- A.Christie

- Heidegger

- Icaza

- Huxley

- Hubble

- Caldwell

- Steinbeck

- Waugh

- Blixen

- Rhys

- J.Roth - Doderer

- Aub

- Malraux-StExupéry

- DBarnes-NWest

- 1940-1950

- 1940s

- Chandler

- Sartre

- Beauvoir

- Mounier

- Borges

- McCullers

- Camus

- Horkheimer - Adorno

- Cela

- Wright

- Bellows - Hopper - duBois

- Gödel - Türing

- Bataille

- Char-Michaux

- Bogart

- Trevor

- Brecht

- Merleau-Ponty - Ponge

- Simenon

- Aragon

- Algren - Irish

- Bloch

- Mead - Benedict - Linton

- Vogt - Asimov

- Orwell

- Lewin - Mayo - Maslow

- Montherlant

- Buzzati - Pavese

- Vittorini

- Fallada

- Malaparte

- Canetti

- Lowry - Bowles

- Koestler

- Welty

- Boulgakov

- Tamiki - Yôkô

- Weil

- Gadda

- Broch

- Steeman

- 1950-1960

- 1950s

- Moravia

- Rossellini

- Nabokov

- Cioran

- Arendt

- Aron

- Marcuse

- Packard

- Wright Mills

- Vian - Queneau

- Quine - Austin

- Blanchot

- Sarraute - Butor - Duras

- Ionesco - Beckett

- Rogers

- Dürrenmatt

- Sutherland - Bacon

- Peake

- Durrell - Murdoch

- Graham Greene

- Kawabata

- Kerouac

- Bellow - Malamud

- Martin-Santos

- Fanon - Memmi

- Riesman

- Böll - Grass

- Ellison

- Bergman

- Baldwin

- Fromm

- Bradbury - A.C.Clarke

- Tennessee Williams

- Erikson

- Bachmann - Celan - Sachs

- Rulfo-Paz

- Achébé - Soyinka

- Pollock

- Carpentier

- Mishima

- Salinger - Styron

- Pasternak

- Asturias

- O'Connor

- Hoffer

- 1960-1970

- 1960s

- Abe

- Ricoeur

- Roth - Elkin

- Lévi-Strauss

- Burgess

- U.Johnson - C.Wolf

- Heller - Toole

- Naipaul

- J.Rechy - H.Selby

- Antonioni

- T.Wolfe - N.Mailer

- Onetti - Sábato

- Capote

- Vonnegut

- Plath

- Burroughs

- Veneziano

- Godard

- McCarthy - Minsky

- Sillitoe

- Sagan

- Gadamer

- Martin Luther King

- Laing

- Lenz

- P.K.Dick - Le Guin

- Lefebvre

- Althusser

- Lacan

- Foucault

- Jankélévitch

- Goffman

- Barthes

- Dolls

- Ellis

- Cortázar

- Warhol

- Berne

- Grossman

- McLuhan

- Soljénitsyne

- Lessing

- Leary

- Kuhn

- HarperLee

- Fuentes

- 1970-1980

- 1970s

- Habermas

- Handke

- GarciaMarquez

- Deleuze

- Derrida

- Beck

- Satir

- Kundera

- Hrabal

- Didion

- Guinzbourg

- Lovelock

- Vietnam

- H.S.Thompson - Bukowski

- Pynchon

- E.T.Hall

- Bateson - Watzlawick

- Carver

- Irving

- Milgram

- VargasLlosa

- Puig - Donoso

- Lasch-Sennett

- Crozier - Touraine

- Friedan-Greer

- Jacob-Monod

- Dawkins

- Beattie - Phillips

- Gaddis

- Rawls

- Zinoviev

- H.Searles

- Ballard

- Jong

- Kôno

- Calvino

- Ballester-Delibes

- ASchmidt

- 1980-1990

- 1990-2000

- Lectures XXIe

- Promenades

- Paysages

- Contact

- 1920s

- Breton

- Tanguy - Ernst

- Eluard

- Jacob - Cocteau

- Gramsci

- Lukacs

- Hesse

- Woolf

- Valéry

- Alain

- Mansfield

- Lawrence

- Bachelard

- Zweig

- Larbaud - Morand

- Döblin

- Musil

- Mann

- Colette

- Mauriac

- MartinDuGard

- Spengler

- Joyce

- Pabst

- S.Lewis

- Dreiser

- Pound

- Heisenberg

- TS Eliot

- Supervielle - Reverdy

- Sandburg

- Duhamel - Romains

- Giraudoux - Jouhandeau

- Svevo - Pirandello

- Harlem - Langston Hughes

- Cassirer

- Lovecraft

- Zamiatine

- W.Benjamin

- Chesterton

- Akutagawa

- Tanizaki

Vorticisme, Ezra Pound (1885-1972), "Hugh Selwyn Mauberley" (1920), "Guide to Kulchur" (1938), "Los Cantos" (1919-1959) - ...

Last Update : 12/31/2020

Ezra Pound est considéré comme l'un des plus grands poètes du XXe siècle, et ses "Cantos", auxquelles il travailla de la Première Guerre mondiale à la fin des années 50, demeurent son chef d'oeuvre. Il fut l'ami de T.S.Eliot et de J.Joyce, qu'il défendit alors qu'ils étaient inconnus, il a joué un rôle important dans la publication d'Ulysse, tout en restant une personnalité très contestée, - et très contestable dans certaines de ses conséquences d'artiste : comme on sait, le double refus de l'époque et de l'hédonisme allait conduire Pound au fascisme, tout comme un certain dégoût et de l'Amérique et de l'Angleterre ("l'imbécillité infinie et ineffable de l'empire britannique", écrit-il en 1931). Et pourtant, on a pu évoquer l'américanisme profond de Pound sous la forme d'une réaction parfois naïve, parfois outrancière contre l'inculture dominante ("knownothingism") du pays natal dont le poète s'est exilé à vingt-trois ans, sa ruée sur la culture classique et européenne, sa pseudo revanche furieusement proclamée sur une Amérique haïssable, sa propension à se forger une érudition qui laisse délibérément de côté et l'histoire des idées et de la pensée au profit de la connaissance de la sensibilité des hommes qui vécurent au temps des troubadours, de Dante, etc. et des formes et moyens de leur expression ...

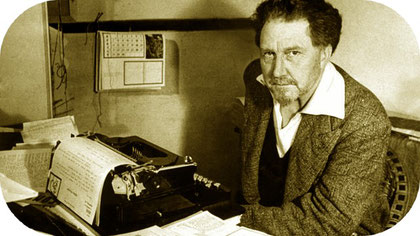

De la bohème des années 20 à la solitude de l'asile psychiatrique de Washington, où il fut enfermé de 1945 à 1958 pour avoir collaboré à la radio mussolinienne, Ezra Pound a essayé sur la littérature américaine; dont il avait quitté le continent dès 1908, deux traitements de choc, l' "imagisme" puis le "vorticisme". Il s'était imposé un devoir moral, celui de conserver aux mots la valeur perdue dans une société devenue mercantile, faire de l'art et de la poésie "une sorte d'énergie proche de l'électricité ou de la radioactivité, une force capable de transfuser, de souder". Il fallait en premier redonner à la littérature son rôle primordial, qui est d'inciter l'humanité à continuer de vivre. Et le retour aux sources qu'il entreprend, hétérogène, marque son refus d'une civilisation de son temps éminemment corrompue : "The Spirit of Romance" (1910), "A Lume Spento" (1908), "Personae" (1909), "Hugh Selwyn Mauberley" (1920).

Contre cette désagrégation du monde et du langage, Pound entreprendra "Cantos", oeuvre de sa vie, débutée en 1915 et à laquelle il travaillera jusqu'à sa mort. Conçus sur le thème de la descente aux enfers, sur un schéma inspiré de la Divine Comédie, de Dante, les Cantos sont écrits en plusieurs langues et sur des tonalités différentes, composant la double chronique de l'écroulement du monde et de sa recomposition par le langage....

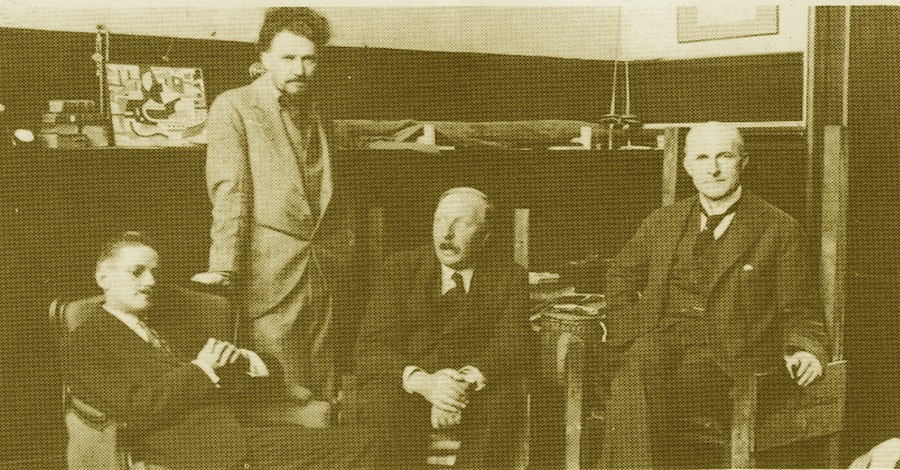

James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford et John Quinn, conférence au sommet marquant la création de la Transatlantic Review, dans le studio parisien de Pound, en 1923...

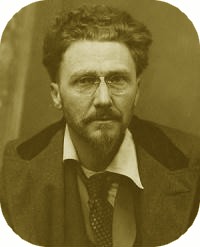

Ezra Pound (1885-1972)

Fils d’un fonctionnaire quaker, Pound (Ezra Loomis) est diplômé en littérature comparée en 1905, mais renonce à la pédagogie, fuit les Etats-Unis pour Venise, où il publie en 1908 son premier volume de vers. Il gagne Londres, y mène une vie de bohème, puis se fixe à Paris en 1920, loin de la stérilité spirituelle de l'ère industrielle qu'offre les Etats-Unis, et devient un catalyseur, avec un extraordinaire flair littéraire pour découvrir les nouveaux talents : il se lie avec Ford Madox Ford (1873-1937), T. E. Hulme (1883-1917), Wyndham Lewis (1884-1957), découvre T. S. Eliot, dont il impose "The Waste Land", puis soutient James Joyce, dont "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man". C'est alors que s'élabore, avec Richard Aldington et Robert Frost, un mouvement poétique relativement bref, l’ "imagisme" (Des imagistes, An Anthology, 1914), qui déplace l’accent du fond sur la forme et entend enfermer des moments d'émotion dans des poèmes courts, lapidaires: "une image est ce qui présente un contenu à la fois intellectuel et émotionnel avec une rapidité fulgurante". L’imagisme veut que la poésie utilise le langage commun, crée de nouveaux rythmes, cristallise en images le phénomène poétique. Son effet sera considérable sur la poésie anglo-américaine.

En 1915, Pound lance le "vorticisme", qui entend considérer l’art comme « une sorte d’énergie proche de l’électricité ou de la radioactivité, une force capable de transfuser, de souder ». Il commence alors à élaborer une oeuvre controversée, les "Cantos", s'installe en Italie en 1924, se rapproche imprudemment du fascisme qui lui valent en 1945 d'être inculpé de trahison. Emprisonné à Pise, il y écrit les "Cantos pisans", mais sans plus croire possible l'avènement d'un paradis, comme dans La Divine comédie...

"THE CANTOS" (1919-1955)

La publication des Cantos s`est échelonnée de 1919 à 1959, et n'est pas encore achevée en 1966. La composition des Cantos occupa la plus grande partie de la vie du poète, et fut sans doute influencée, voire perturbée, par cette vie elle-même. L`ídée du recueil est née au cours de la période anglaise de Pound qui, rejetant l'Amérique, a vécu en Angleterre de 1908 à 1921. Si quelques autres cantos ont dû être écrits à Paris, où Pound a séjourné de 1921 à 1924, la plus grande part est cependant le fruit du séjour du poète en Italie (1925-1945), où il s`était établi à Rapallo, et où il devint rapidement un fasciste militant, écrivant des œuvres de propagande pour le régime mussolinien, allant jusqu'à utiliser dans ses poésies, preuve d'un aveuglement total, la chronologie de l'ère fasciste, et, pendant la guerre, faisant des conférences à la radio italienne....

Canto I

And then went down to the ship,

Set keel to breakers, forth on the godly seas, and

We set up mast and sail on that swart ship,

Bore sheep aboard her, and our bodies also

Heavy with weeping, and winds from sternward

Bore us out onward with bellying canvas,

Circe’s this craft, the trim-coifed goddess.

Then sat we amidships, wind jamming the tiller,

Thus with stretched sail, we went over sea till day’s end.

Sun to his slumber, shadows o’er all the ocean,

Came we then to the bounds of deepest water,

To the Kimmerian lands, and peopled cities

Covered with close-webbed mist, unpierced ever

With glitter of sun-rays

Nor with stars stretched, nor looking back from heaven

Swartest night stretched over wretched men there.

The ocean flowing backward, came we then to the place

Aforesaid by Circe.

Here did they rites, Perimedes and Eurylochus,

And drawing sword from my hip

I dug the ell-square pitkin;

Poured we libations unto each the dead,

First mead and then sweet wine, water mixed with white flour.

Then prayed I many a prayer to the sickly death’s-heads;

As set in Ithaca, sterile bulls of the best

For sacrifice, heaping the pyre with goods,

A sheep to Tiresias only, black and a bell-sheep.

Dark blood flowed in the fosse,

Souls out of Erebus, cadaverous dead, of brides

Of youths and of the old who had borne much;

Souls stained with recent tears, girls tender,

Men many, mauled with bronze lance heads,

Battle spoil, bearing yet dreory arms,

These many crowded about me; with shouting,

Pallor upon me, cried to my men for more beasts;

Slaughtered the herds, sheep slain of bronze;

Poured ointment, cried to the gods,

To Pluto the strong, and praised Proserpine;

Unsheathed the narrow sword,

I sat to keep off the impetuous impotent dead,

Till I should hear Tiresias.

But first Elpenor came, our friend Elpenor,

Unburied, cast on the wide earth,

Limbs that we left in the house of Circe,

Unwept, unwrapped in sepulchre, since toils urged other.

Pitiful spirit. And I cried in hurried speech:

“Elpenor, how art thou come to this dark coast?

“Cam’st thou afoot, outstripping seamen?”

And he in heavy speech:

“Ill fate and abundant wine. I slept in Circe’s ingle.

“Going down the long ladder unguarded,

“I fell against the buttress,

“Shattered the nape-nerve, the soul sought Avernus.

“But thou, O King, I bid remember me, unwept, unburied,

“Heap up mine arms, be tomb by sea-bord, and inscribed:

“A man of no fortune, and with a name to come.

“And set my oar up, that I swung mid fellows.”

And Anticlea came, whom I beat off, and then Tiresias Theban,

Holding his golden wand, knew me, and spoke first:

“A second time? why? man of ill star,

“Facing the sunless dead and this joyless region?

“Stand from the fosse, leave me my bloody bever

“For soothsay.”

And I stepped back,

And he strong with the blood, said then: “Odysseus

“Shalt return through spiteful Neptune, over dark seas,

“Lose all companions.” And then Anticlea came.

Lie quiet Divus. I mean, that is Andreas Divus,

In officina Wecheli, 1538, out of Homer.

And he sailed, by Sirens and thence outward and away

And unto Circe.

Venerandam,

In the Cretan’s phrase, with the golden crown, Aphrodite,

Cypri munimenta sortita est, mirthful, orichalchi, with golden

Girdles and breast bands, thou with dark eyelids

Bearing the golden bough of Argicida. So that:

En 1919 : "Cantos I-II-III" (première version) publiés in "Quia pauper amaví" à Londres. Et en édition séparée de "The Fourth Canto". En 1921 : "Cantos IV-V-VI-VII" in "Poems 1918-1921" (New York)....

En 1925, "A Draft of XVI Cantos" (Paris), puis en 1928, "A Draft of the Cantos 17-27" (Londres). En 1930, "A Draft of XXX Cantos" (Paris), en 1934, "Eleven New Cantos", en fait XXXI-XLI (New York), puis en 1937, "The Fifth Decad of Cantos XLII-LI (Londres).

Canto IV

Palace in smoky light,

Troy but a heap of smouldering boundary stones,

ANAXIFORMINGES! Aurunculeia!

Hear me. Cadmus of Golden Prows!

The silver mirrors catch the bright stones and flare,

Dawn, to our waking, drifts in the green cool light;

Dew-haze blurs, in the grass, pale ankles moving.

Beat, beat, whirr, thud, in the soft turf

under the apple trees,

Choros nympharum, goat-foot, with the pale foot alternate;

Crescent of blue-shot waters, green-gold in the shallows,

A black cock crows in the sea-foam;

And by the curved, carved foot of the couch,

claw-foot and lion head, an old man seated

Speaking in the low drone…:

Ityn!

Et ter flebiliter, Ityn, Ityn!

And she went toward the window and cast her down,

“All the while, the while, swallows crying:

Ityn!

“It is Cabestan’s heart in the dish.”

“It is Cabestan’s heart in the dish?”

“No other taste shall change this.”

And she went toward the window,

the slim white stone bar

Making a double arch;

Firm even fingers held to the firm pale stone;

Swung for a moment,

and the wind out of Rhodez

Caught in the full of her sleeve.

. . . the swallows crying:

‘Tis. ‘Tis. ‘Ytis!

Actæon…

and a valley,

The valley is thick with leaves, with leaves, the trees,

The sunlight glitters, glitters a-top,

Like a fish-scale roof,

Like the church roof in Poictiers

If it were gold.

Beneath it, beneath it

Not a ray, not a slivver, not a spare disc of sunlight

Flaking the black, soft water;

Bathing the body of nymphs, of nymphs, and Diana,

Nymphs, white-gathered about her, and the air, air,

Shaking, air alight with the goddess

fanning their hair in the dark,

Lifting, lifting and waffing:

Ivory dipping in silver,

Shadow’d, o’ershadow’d

Ivory dipping in silver,

Not a splotch, not a lost shatter of sunlight.

Then Actæon: Vidal,

Vidal. It is old Vidal speaking,

stumbling along in the wood,

Not a patch, not a lost shimmer of sunlight,

the pale hair of the goddess.

The dogs leap on Actæon,

“Hither, hither, Actæon,”

Spotted stag of the wood;

Gold, gold, a sheaf of hair,

Thick like a wheat swath,

Blaze, blaze in the sun,

The dogs leap on Actæon.

Stumbling, stumbling along in the wood,

Muttering, muttering Ovid:

“Pergusa… pool… pool… Gargaphia,

“Pool… pool of Salmacis.”

The empty armour shakes as the cygnet moves.

Thus the light rains, thus pours, e lo soleills plovil

The liquid and rushing crystal

beneath the knees of the gods.

Ply over ply, thin glitter of water;

Brook film bearing white petals.

The pine at Takasago

grows with the pine of Isé!

The water whirls up the bright pale sand in the spring’s mouth

“Behold the Tree of the Visages!”

Forked branch-tips, flaming as if with lotus.

Ply over ply

The shallow eddying fluid,

beneath the knees of the gods.

Torches melt in the glare

set flame of the corner cook-stall,

Blue agate casing the sky (as at Gourdon that time)

the sputter of resin,

Saffron sandal so petals the narrow foot: Hymenæus Io!

Hymen, Io Hymenæe! Aurunculeia!

One scarlet flower is cast on the blanch-white stone.

And So-Gyoku, saying:

“This wind, sire, is the king’s wind,

This wind is wind of the palace,

Shaking imperial water-jets.”

And Hsiang, opening his collar:

“This wind roars in the earth’s bag,

it lays the water with rushes.”

No wind is the king’s wind.

Let every cow keep her calf.

“This wind is held in gauze curtains…”

No wind is the king’s…

The camel drivers sit in the turn of the stairs,

Look down on Ecbatan of plotted streets,

“Danaë! Danaë!

What wind is the king’s?”

Smoke hangs on the stream,

The peach-trees shed bright leaves in the water,

Sound drifts in the evening haze,

The bark scrapes at the ford,

Gilt rafters above black water,

Three steps in an open field,

Gray stone-posts leading…

Père Henri Jacques would speak with the Sennin, on Rokku,

Mount Rokku between the rock and the cedars,

Polhonac,

As Gyges on Thracian platter set the feast,

Cabestan, Tereus,

It is Cabestan’s heart in the dish,

Vidal, or Ecbatan, upon the gilded tower in Ecbatan

Lay the god’s bride, lay ever, waiting the golden rain.

By Garonne. “Saave!”

The Garonne is thick like paint,

Procession,—“Et sa’ave, sa’ave, sa’ave Regina!”—

Moves like a worm, in the crowd.

Adige, thin film of images,

Across the Adige, by Stefano, Madonna in hortulo,

As Cavalcanti had seen her.

The Centaur’s heel plants in the earth loam.

And we sit here…

there in the arena…

Selon les propos de Pound reproduits par W. B. Yeats, - et antérieurs à la rédaction des premiers cantos -, le projet originel aurait été le suivant : "Il n'y aura pas d'intrigue, pas de successions d'événements, pas de logique interne de l`œuvre, mais seulement deux thèmes, la descente aux Enfers telle qu'on la trouve dans Homère et une métamorphose d'Ovide, à quoi se mêleront des personnages ou types historiques du Moyen Age et des temps modernes." Et de fait, les deux thèmes indiqués constituent la substance même des Cantos I, ssans doute le plus classique de tous, puisque, à l'exception des cinq dernières lignes, il s'en tient à un seul sujet. Mais à noter que c`est tout simplement une adaptation anglaise d'une vieille traduction en latin d`un passage de la Nekuya d'Homère, - le titre donné au chant XI de l’Odyssée relatant l’invocation du défunt devin Tirésias par Ulysse qui cherche alors désespérément à rentrer à Ithaque.

Dans le Cantos II, à côté de la réévocation d'une métamorphose d'Ovide, apparaissent les noms de Robert Browning et d”Eléonore d'Aquitaine). Les deux thèmes, descente aux Enfers et métamorphose, reviennent constamment tout au long du recueil, et le premier d'entre eux, lié aux personnages homériques d'Ulysse et de Tirésias, impose le rapprochement avec les chefs-d'œuvre de deux écrivains dont Pound a encouragé les débuts, "Ulysse" de James Joyce (qui jugea plus tard les Cantos illisibles) et "La Terre vaine", de T. S. Eliot, deux œuvres conçues dans la même période que les Cantos, et qui participent du même courant de recherches formelles.

La descente chez les morts est vécue ici comme une redécouverte de toute la tradition culturelle que l`artiste du XXe siècle se doit, selon Pound, d'assumer, de refaire sienne. Cette culture, elle est tout autant littéraire qu'historique, rassemblant à côté des héros littéraires, tant bien que mal, les héros de l'histoire. Homère son Odyssée et ses Hymnes, Ovide et les élégiaques romains, les troubadours (Arnaut Daniel, Bertrand de Born), Dante, Villon et puis certains poètes contemporains, amis de Pound dans sa période anglaise, vont ainsi côtoyer Eléonore d'Aquitaine, Inez de Castro, Cunizza, les condottieri et les papes du quattrocento, Sigismond Malatesta, Pie II, Alexandre Borgia, mais aussi les Américains John Adams, second président des Etats-Unis (généralement considéré comme réactionnaire, il sera un des héros favoris de Pound), Jefferson, Van Buren, et les empereurs chinois, et comme naturellement, Mussolini (que les Cantos písans nomment rarement, mais désignent fort clairement). L`Afrique aussi prendra sa place sous la forme notamment de la cité (qui fut réelle) de Wagadou, dont Pound a fait une sorte de mythe du Phénix. Une bien étrange encyclopédie de la culture humaine mais toute personnelle, avec ses préjugés contre par exemple la Renaissance ou Shakespeare, etc.

Enfin, dès le début, la conception des Cantos, s'affirme un parallèle moderne avec "La Divine comédie" de Dante, et la division tripartite en Enfer, Purgatoire et Paradis indiquée par Pound lui-même. pour qui les Cantos písans constitueront le début de son Paradis. Pound n'est pas le moins du monde chrétien, et, s`il recherche cependant une certaine religiosité après s'être tourné vers, semble-t-il, les archétypes platoniciens, c`est dans une curieuse conversion au confucianisme que cette recherche débouchera (donc, un paradis, mais terrestre)...

De la technique des Cantos, on a pu identifier un usage massif, répété indéfiniment, inlassablement, des mêmes procédés : ce principe esthétique affirmé dès 1908, avant même que se soit constituée l'école imagiste, "peindre les choses comme je les vois", - et non comme on les sent ou comme on les éprouve (lettre à William Carlos Williams) -, représenter donc au lecteur des choses, des faits, des éléments concrets ; éviter tout mot qui n'est pas strictement indispensable et échapper par tous les moyens à l'abstraction ; introduire systématiquement un principe de discontinuité dans le poème, - des images ou des idéogrammes de différentes époques, de différentes cultures, se succédant soudainement sans aucune transition, des morceaux de conversation courante d'aujourd'hui ou des passages abrupts de l`anglais à d'autres langues (français, italien, allemand). Soit une combinaison volontaire d'éléments hétérogènes qui laisserait peu de place au lyrisme au sens traditionnel du terme ....

T.S.Eliot, dans son chef-d'œuvre, "The Waste Land" (La Terre vaine, 1922), - dédié à Pound et le premier long poème moderniste écrit en réponse à la Première Guerre mondiale, "Antwderp" de Ford Madox Ford -, utilise ces mêmes techniques, mais avec sans doute un plus riche contenu humain que notre poète ...

I. The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

Summer surprised us, coming over the Starnbergersee

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the colonnade,

And went on in sunlight, into the Hofgarten,

And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Bin gar keine Russin, stamm’ aus Litauen, echt deutsch.

And when we were children, staying at the archduke’s,

My cousin’s, he took me out on a sled,

And I was frightened. He said, Marie,

Marie, hold on tight. And down we went.

In the mountains, there you feel free.

I read, much of the night, and go south in the winter.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

Frisch weht der Wind

Der Heimat zu,

Mein Irisch Kind,

Wo weilest du?

“You gave me hyacinths first a year ago;

“They called me the hyacinth girl.”

—Yet when we came back, late, from the Hyacinth garden,

Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

Öd’ und leer das Meer.

(...)

En 1940, "Cantos LII-LXXI" (Londres), puis en 1948, ""Pisan Cantos" (U.S.A.), en fait LXXIV-LXXXIV, les Cantos LXXII et LXXIII n'ayant pas été jusqu'ici publiés par l`auteur, probablement en raison de leur contenu politique. Toujours en 1948, "Cantos" (New York puis Londres), la première édition complète des cantos écrits jusque-là. J.H. Edwards et W.W.Vasse ajoutèrent à cette édition un " Annotated Index" qui donne le catalogue des noms propres, citations grecques, latines, allemandes, françaises, chinoises, etc., utilisés dans les poèmes, ainsi que des tableaux généalogiques et dynastiques.

La Chine s`installe à la place d'honneur dans les Cantos LII à LXI, pour réapparaître ensuite dans le kaléidoscope des Cantos pisans, après avoir fait une première apparition avec le Canto XIII, adaptation ou remaniement à la Ezra Pound de fragments de Confucius. La lecture des manuscrits de l`orientaliste américain Ernest Fenollosa vers 1921 suscita l'intérêt du poète pour la littérature et l'histoire de l`Extrême-Orient, Chine et Japon.

Arrêté par les autorités militaires américaines après la débâcle fasciste (Pound, notons-le, était resté fidèle à Mussolini en 1943-45), Pound écrit les "Cantos písans" en 1945 dans le camp militaire où il avait été intemé avant son transfert aux Etats-Unis. On sait qu'il n'échappa, en 1946, à un procès en haute trahison que parce qu'il fut déclaré fou et interné de 1946 à 1958, internement qui d'ailleurs ne mit aucun obstacle à son travail d'écrivain. Ces détails biographiques se sont transportés directement dans ses poèmes tout comme il se réapproprie et intègre dans son univers, à sa façon, les fragments tirés de ses lectures...

C'est dans ces "Cantos písans" que défilent les images de la guerre, les insultes à froid contre les Alliés, ici nommés les barbares, l'évocation des "20 ans de rêve" que furent pour lui le fascisme italien, les souvenirs de la vie littéraire d'avant-guerre, et le poète lui-même, comme un regard obstiné en face de ce monde ("fourmi solitaire, échappée au naufrage européen, moi l'écrivain", Canto LXXVI), et de fierté de l'œuvre littéraire accomplie (fin du Canto LXXXI).

En 1955, "Sections Rock-Drill" (Milan), soit LXXXV-XCV, en 1959, "Thrones"(Milan), XCVI-CIX....

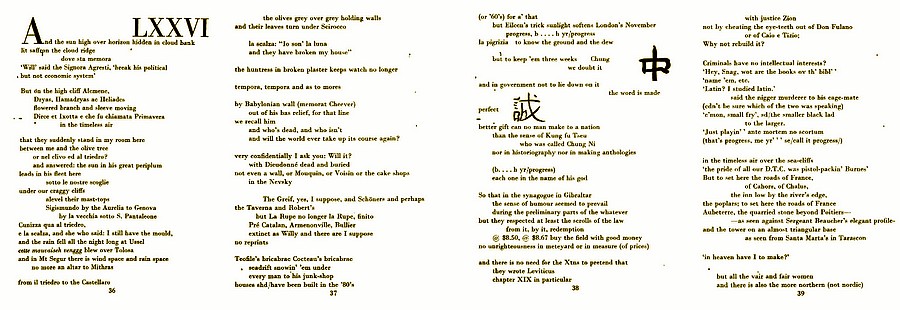

LXXVI

And the sun high over horizon hidden in cloud bank

lit saffron the cloud ridge

dove sta memora

‘Will’ said the Signora Agresti, ‘break his political

'but not economic system’

But on the high cliff Alcmene,

Dryas, Hamadryas ac Heliades

flowered branch and sleeve moving

Dirce et Ixotta e che fu chiamata Primavera

in the timeless air

that they suddenly stand in my room here

between me and the olive tree

or nel clivo ed al triedro ?

and answered: the sun in his great periplum

leads in his fleet here

sotto le nostre scoglie

under our craggy cliffs

alevel their mast-tops

Sigismundo by the Aurelia to Genova

by la vecchia sotto S. Pantaleone

Cunizza qua al triedro,

e la scalza, and she who said: I still have the mould,

and the rain fell all the night long at Ussel

cette mauvaiseh venggg blew over Tolosa

and in Mt Segur there is wind space and rain space

no more an altar to Mithras

from il triedro to the Castellaro

the olives grey over grey holding walls

and their leaves turn under Scirocco

la scalza: “Io son’ la luna

and they have broken my house” ,

the huntress in broken plaster keeps watch no longer

tempora, tempora and as to mores

by Babylonian wall (memorat Cheever)

out of his bas relief, for that line we recall him

and who’s dead, and who isn’t

and will the world ever take up its course again?

very confidentially I ask you: Will it?

with Dieudonné dead and buried

not even a wall, or Mouquin, or Voisin or the cake shops

in the Nevsky

The Greif, yes, I suppose, and Schöners and perhaps

the Taverna and Robert’s

but La Rupe no longer la Rupe, finito

Pré Catalan, Armenonville, Bullier

extinct as Willy and there are I suppose

no reprints

Teofile’s bricabrac Cocteau’s bricabrac

seadrift snowin’ ’em under

every man to his junk-shop

houses shd/have been built in the ’80’s

(or '60's) for a' that

but Eileen's trick sunlight softens London's Novembre

progress, b.... h yr/progress

(.....)

LXXXI

(...)

Saw but the eyes and stance between the eyes,

colour, diastasis,

careless or unaware it had not the

whole tent’s room

nor was place for the full Eidos

interpass, penetrate

casting but shade beyond the other lights

sky’s clear

night’s sea

green of the mountain pool

shone from the unmasked eyes in half-mask’s space.

What thou lovest well remains,

the rest is dross

What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee

What thou lov’st well is thy true heritage

Whose world, or mine or theirs

or is it of none?

First came the seen, thus the palpable

Elysium, though it were in the halls of hell,

What thou lovest well is thy true heritage

What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee

The ant’s a centaur in his dragon world.

Pull down thy vanity, it is not man

Made courage, or made order, or made grace,

Pull down thy vanity, I say pull down.

Learn of the green world what can be thy place

In scaled invention or true artistry,

Pull down thy vanity,

Paquin pull down!

The green casque has outdone your elegance.

‘Master thyself, then others shall thee beare’

Pull down thy vanity

Thou art a beaten dog beneath the hail,

A swollen magpie in a fitful sun,

Half black half white

Nor knowst’ou wing from tail

Pull down thy vanity

How mean thy hates

Fostered in falsity,

Pull down thy vanity,

Rathe to destroy, niggard in charity.

Pull down thy vanity,

I say pull down.

But to have done instead of not doing

this is not vanity

To have, with decency, knocked

That a Blunt should open

To have gathered from the air a live tradition

or from a fine old eye the unconquered flame

This is not vanity.

Here error is all in the not done,

all in the diffidence that faltered.

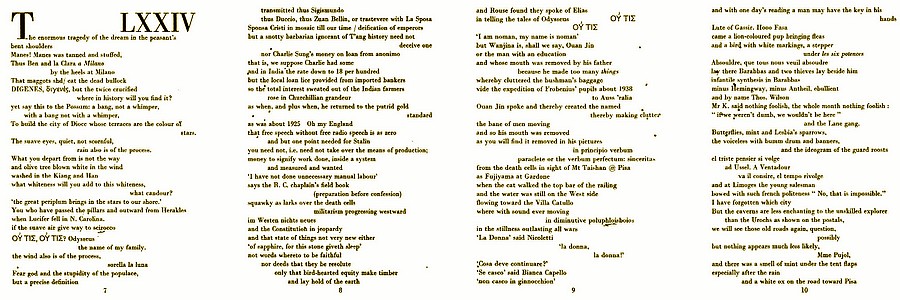

"Hugh Selwyn Mauberley" (1920)

"Hugh Selwyn Mauberley" est un long poème d'Ezra Pound. Il a été considéré comme un tournant dans la carrière de Pound (par F.R. Leavis et d'autres), et son achèvement a été rapidement suivi par son départ d'Angleterre. Le nom "Selwyn" pourrait être un hommage à Selwyn Image, membre du Rhymers' Club. Le nom et la personnalité du sujet titulaire rappellent également le personnage principal de T. S. Eliot dans The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

C`est donc la dernière œuvre poétique importante de Pound, indépendante des "Cantos", dont la publication avait commencé en 1917, et d'une qualité poétique considérée comme plus rigoureuse que celle des Cantos. Elle est divisée en deux parties, la première où l'auteur et le personnage imaginaire se confondent, la seconde, où, au contraire, l`auteur se sépare de son personnage et le juge. L`ensemble est tout à la fois un bilan et un art poétique.

La première partie comprend douze brefs poèmes, elle s'ouvre par "E. P. Ode pour l`élection de son sépulcre" (le titre, repris de Ronsard, est en français dans le texte). ..

« Sa propre Pénélope était Flaubert. ll jetait sans cesse sa ligne sur les rivages d'îles endurcies ; / il portait plus d`attention à l'élégance des cheveux de Circé / qu`aux devises des cadrans solaires. / Indifférent à la marche du temps. / Il disparut de la mémoire des hommes en l`an trentiesme / De "son cage"; de son cas / n`ajoute rien à la couronne des Muses." Des vers, qui sont très vite devenus célèbres parmi les amateurs de la poésie de Pound ..

ODE POUR SELECTION DE SON SEPULCHRE

OR three years, out of key with his time,

He strove to resuscitate the dead art

Of poetry ; to maintain " the sublime "

In the old sense. Wrong from the start -

No hardly, but, seeing he had been born

In a half savage country, out of date ;

Bent resolutely on wringing lilies from the acorn ;

Capaneus ; trout for factitious bait ;

"Idmen gar toi panth, os eni Troie"

Caught in the unstopped ear ;

Giving the rocks small lee-way

The chopped seas held him, therefore, that year.

His true Penelope was Flaubert,

He fished by obstinate isles ;

Observed the elegance of Circe's hair

Rather than the mottoes on sun-dials.

Unaffected by " the march of events,"

He passed from men's memory in "l'an trentiesme"

De "son cage" ; the case presents

No adjunct to the Muses' diadem.

Un second poème lui succède, de trois quatrains, et non moins célèbres ...

"L'époque exigeait une image/ De sa grimace précipitée, / Quelque chose qui plût à la scène moderne, / Non pas, certainement pas, la grâce attique; / Non, à coup sûr non, les rêveries obscures / Du regard intérieur; / Plutôt des mensonges / Que la paraphrase des classiques ! / L'époque exigeait surtout un moule de plâtre/ Coulé à toute vitesse, / Une prose cinématographique, mais sûrement pas l`albâtre / D'une rime bien sculptée."

The age demanded an image

Of its accelerated grimace,

Something for the modern stage,

Not, at any rate, an Attic grace;

Not, not certainly, the obscure reveries

Of the inward gaze;

Better mendacities

Than the classics in paraphrase!

The “age demanded” chiefly a mould in plaster,

Made with no loss of time,

A prose kinema, not, not assuredly, alabaster

Or the “sculpture” of rhyme.

Le troisième poème développe ce thème de l'art rendu impossible par les exigences de l'époque; on y trouve, au sixième quatrain, une attaque explicite contre la démocratie...

The tea-rose, tea-gown, etc.

Supplants the mousseline of Cos,

The pianola “replaces”

Sappho’s barbitos.

Christ follows Dionysus,

Phallic and ambrosial

Made way for macerations;

Caliban casts out Ariel.

All things are a flowing,

Sage Heracleitus says;

But a tawdry cheapness

Shall reign throughout our days.

Even the Christian beauty

Defects—after Samothrace;

We see to kalon

Decreed in the market place.

Faun’s flesh is not to us,

Nor the saint’s vision.

We have the press for wafer;

Franchise for circumcision.

All men, in law, are equals.

Free of Peisistratus,

We choose a knave or an eunuch

To rule over us.

A bright Apollo,

tin andra, tin eroa, tina theon,

What god, man, or hero

Shall I place a tin wreath upon?

Le quatrième poème, qui abandonne provisoirement la forme du quatrain, évoque la guerre de 1914-18, et ses horreurs, l'héroïsme prodigué en vain au profit de mensonges et d'infamies...

These fought, in any case,

and some believing, pro domo, in any case ...

Some quick to arm,

some for adventure,

some from fear of weakness,

some from fear of censure,

some for love of slaughter, in imagination,

learning later ...

some in fear, learning love of slaughter;

Died some pro patria, non dulce non et decor” ...

walked eye-deep in hell

believing in old men’s lies, then unbelieving

came home, home to a lie,

home to many deceits,

home to old lies and new infamy;

usury age-old and age-thick

and liars in public places.

Daring as never before, wastage as never before.

Young blood and high blood,

Fair cheeks, and fine bodies;

fortitude as never before

frankness as never before,

disillusions as never told in the old days,

hysterias, trench confessions,

laughter out of dead bellies.

Le cinquième poème, très bref, n'est qu'un appendice du précédent...

There died a myriad,

And of the best, among them,

For an old bitch gone in the teeth,

For a botched civilization.

Charm, smiling at the good mouth,

Quick eyes gone under earth’s lid,

For two gross of broken statues,

For a few thousand battered books.

Avec le sixième poème, intitulé "Yeux glauques " (en français dans le texte), nous revenons aux problèmes littéraires, avec une évocation des préraphaélites anglais et de leur supposé échec...

YEUX GLAUQUES

Gladstone was still respected,

When John Ruskin produced

“Kings Treasuries”; Swinburne

And Rossetti still abused.

Foetid Buchanan lifted up his voice

When that faun’s head of hers

Became a pastime for

Painters and adulterers.

The Burne-Jones cartons

Have preserved her eyes;

Still, at the Tate, they teach

Cophetua to rhapsodize;

Thin like brook-water,

With a vacant gaze.

The English Rubaiyat was still-born

In those days.

The thin, clear gaze, the same

Still darts out faun-like from the half-ruin’d face,

Questing and passive ....

“Ah, poor Jenny’s case” ...

Bewildered that a world

Shows no surprise

At her last maquero’s

Adulteries.

Le septième poème, intitulé "Siena mi fe ; disfecemi Maremma" (citation de Dante) évoque les mouvements littéraires de la fin du XIXe siècle, et le mépris croissant pour l`artiste sérieux, savant, de plus en plus isolé.

SIENA MI FE’, DISFECEMI MAREMMA’”

Among the pickled foetuses and bottled bones,

Engaged in perfecting the catalogue,

I found the last scion of the

Senatorial families of Strasbourg, Monsieur Verog.

For two hours he talked of Gallifet;

Of Dowson; of the Rhymers’ Club;

Told me how Johnson (Lionel) died

By falling from a high stool in a pub ...

But showed no trace of alcohol

At the autopsy, privately performed—

Tissue preserved—the pure mind

Arose toward Newman as the whiskey warmed.

Dowson found harlots cheaper than hotels;

Headlam for uplift; Image impartially imbued

With raptures for Bacchus, Terpsichore and the Church.

So spoke the author of “The Dorian Mood,”

M. Verog, out of step with the decade,

Detached from his contemporaries,

Neglected by the young,

Because of these reveries.

Le huitième poème, intitulé "Brembaum", très court, est, malheureusement, une première manifestation de l'antisémitisme dans la poésie de Pound...

BRENNEBAUM

The sky-like limpid eyes,

The circular infant’s face,

The stiffness from spats to collar

Never relaxing into grace;

The heavy memories of Horeb, Sinai and the forty years,

Showed only when the daylight fell

Level across the face

Of Brennbaum “The Impeccable.”

Le neuvième, intitulé "Mr. Nixon", est une satire de l'art commercialisé, soumis aux impératifs de l'argent...

MR. NIXON

In the cream gilded cabin of his steam yacht

Mr. Nixon advised me kindly, to advance with fewer

Dangers of delay. “Consider

”Carefully the reviewer.

“I was as poor as you are;

“When I began I got, of course,

“Advance on royalties, fifty at first,” said Mr. Nixon,

“Follow me, and take a column,

“Even if you have to work free.

“Butter reviewers. From fifty to three hundred

“I rose in eighteen months;

“The hardest nut I had to crack

“Was Dr. Dundas.

“I never mentioned a man but with the view

“Of selling my own works.

“The tip’s a good one, as for literature

“It gives no man a sinecure.”

And no one knows, at sight a masterpiece.

And give up verse, my boy,

There’s nothing in it.”

* * * *

Likewise a friend of Bloughram’s once advised me:

Don’t kick against the pricks,

Accept opinion. The “Nineties” tried your game

And died, there’s nothing in it.

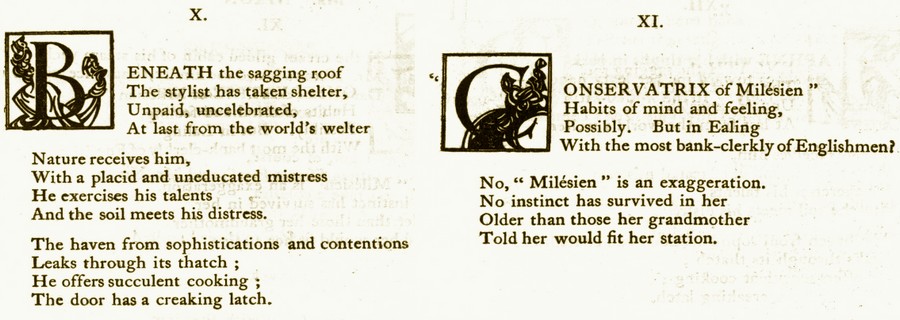

Le dixième poème évoque l'artiste solitaire, "non stipendié, inconnu", à l'écart de la "tempête mondiale", et qui s`obstine...

Beneath the sagging roof

The stylist has taken shelter,

Unpaid, uncelebrated,

At last from the world’s welter

Nature receives him,

With a placid and uneducated mistress

He exercises his talents

And the soil meets his distress.

The haven from sophistications and contentions

Leaks through its thatch;

He offers succulent cooking;

The door has a creaking latch.

Les onzième et douzième poèmes évoquent, le premier, les femmes cultivées (« La Milésienne"), elles aussi artistiquement stériles, et les cercles cultivés et snobs, pour qui l`artiste vrai (Pound ou Mauberley) est inacceptable...

XI

“Conservatrix of Milésien”

Habits of mind and feeling,

Possibly. But in Ealing

With the most bank-clerkly of Englishmen?

No, “Milésian” is an exaggeration.

No instinct has survived in her

Older than those her grandmother

Told her would fit her station.

XII

“Daphne with her thighs in bark

Stretches toward me her leafy hands,”—

Subjectively. In the stuffed-satin drawing-room

I await The Lady Valentine’s commands,

Knowing my coat has never been

Of precisely the fashion

To stimulate, in her,

A durable passion;

Doubtful, somewhat, of the value

Of well-gowned approbation

Of literary effort,

But never of The Lady Valentine’s vocation:

Poetry, her border of ideas,

The edge, uncertain, but a means of blending

With other strata

Where the lower and higher have ending;

A hook to catch the Lady Jane’s attention,

A modulation toward the theatre,

Also, in the case of revolution,

A possible friend and comforter.

* * * *

Conduct, on the other hand, the soul

“Which the highest cultures have nourished”

To Fleet St. where

Dr. Johnson flourished;

Beside this thoroughfare

The sale of half-hose has

Long since superseded the cultivation

Of Pierian roses.

Enfin, "Envoi" ( 1919) résume tous les thèmes de la première partie, en les concluant par l'oubli définitif vers lequel s`en va l'artiste véritable....

Go, dumb-born book,

Tell her that sang me once that song of Lawes:

Hadst thou but song

As thou hast subjects known,

Then were there cause in thee that should condone

Even my faults that heavy upon me lie

And build her glories their longevity.

Tell her that sheds

Such treasure in the air,

Recking naught else but that her graces give

Life to the moment,

I would bid them live

As roses might, in magic amber laid,

Red overwrought with orange and all made

One substance and one colour

Braving time.

Tell her that goes

With song upon her lips

But sings not out the song, nor knows

The maker of it, some other mouth,

May be as fair as hers,

Might, in new ages, gain her worshippers,

When our two dusts with Waller's shall be laid,

Siftings on siftings in oblivion,

Till change hath broken down

All things save Beauty alone.

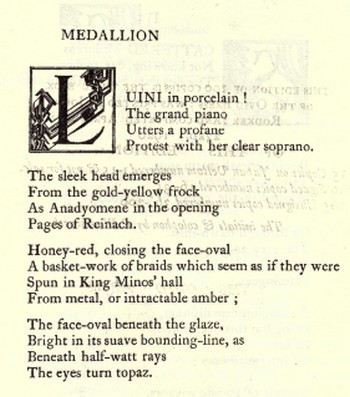

La seconde partie, composée de cinq poèmes seulement, reprend et développe certains vers de la première partie, mais cette fois du point de vue du seul Mauberley, comme un contrepoint ironique.

Le premier poème fait ainsi écho au poème du début, mais Mauberley, dont l`art "n`est qu'un art du profit", est défini : "Un Piero della Francesca / privé de la couleur / Un Pisanello auquel a manqué le métier nécessaire / Pour forger l'Achaïe." Dans le second poème, le héros comprend qu'il lui a manqué d'avoir une passion active, que tout amour véritable lui a fait défaut. Le troisième, "The Age demanded", répond au second poème de la première partie. Mais Mauberley a échoué, il n`a abouti qu'à une "olympienne ataraxie", et a finalement été exclu de l'univers des écrivains.

Le quatrième poème évoquant des voyages vers "Des Moluques éparses", se ferme par l'épigraphe à mettre sur la tombe de Mauberley ...

"Ici se noya / Un hédoniste" (I was / And I no more exist; / Here drifted / An hedonist).

Enfin, le dernier poème, "Médaillon", illustre ce qui reste de cette aventure manquée : un médaillon. Le poème marque donc tout aussi fortement l'opposition de Pound à son époque, aux goûts et au laisser-aller esthétique de cette époque, que son refus de devenir simplement un Mauberley, un solitaire vaincu et paresseux. Comme on sait, le double refus de l'époque et de l'hédonisme allait malheureusement conduire Pound au fascisme...